Geoengineering’s Quiet Beginnings in America

Controlling the weather has long been discussed by powerful people, with Lyndon Johnson saying in 1961 that the US “…would propose cooperative efforts between all nations in weather predictions and eventually in weather control…” During the Vietnam War, the US military caused massive typhoons along the Ho Chi Minh Trail as part of Operation Popeye, marking a very real weaponization of weather. However, serious talks of mass-scale weather control really ramped up in the 1990s, when the seeds of today’s heated debates about stratospheric aerosol injections (SAI), geoengineering, and weather modification were sown. While these topics have exploded into public consciousness recently, they were already simmering in scientific circles, government reports, and occasional media coverage during the decade. Fueled by growing concerns about global warming and a natural volcanic event, the 1990s marked the genesis of geoengineering as a serious, if speculative, idea. This first part of our series uncovers the American news stories from that era, revealing the early experiments, policy discussions, and the roots of public skepticism that foreshadowed today’s “chemtrail” conspiracies.

Cloud-Seeding Is Nothing New

Cloud seeding, a weather modification technique that introduces substances like silver iodide or dry ice into clouds to enhance precipitation, had been practiced in the U.S. since the 1940s. The practice was particularly prominent in the Mountain West and Midwest, following the Dust Bowl era of the 1950s.

These programs aimed to enhance precipitation for agricultural benefits and water resource management. By the 1990s, several Midwestern states were engaged in operational cloud-seeding programs, primarily to boost rainfall for agriculture or to increase snowpack for water supply.

The North Dakota Cloud Modification Project, one of the most prominent cloud-seeding programs in the Midwest during the 1990s, used aircraft to disperse silver iodide for both precipitation enhancement and hail suppression. While ground-based delivery was also used, aircraft were preferred for their ability to target specific cloud formations at higher altitudes, ensuring precise delivery of seeding agents. Other states like Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma, which maintained operational cloud-seeding programs in the 1990s, also employed aircraft for seeding, particularly during drought periods.

A 1994 San Francisco Chronicle article detailed California’s use of silver iodide to boost rainfall, a state-funded effort that sparked local debates over efficacy and environmental impact. Similarly, a 1995 Casper Star-Tribune piece cited a Wyoming cloud-seeding program that claimed 5–10% snowpack increases (Wyoming Weather Modification Pilot Program, 1995). These programs, while localized, fed public curiosity about human control over weather. If the government is willing to spray our skies with silver iodide, what else might they consider putting into the atmosphere?

The Mount Pinatubo Catalyst

The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines was a turning point for altering the weather with more than just silver iodide. By injecting 15–20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, the volcano created aerosols that cooled global temperatures by about 0.5°C for over a year. A 1992 Science magazine article, widely discussed in U.S. media, framed Pinatubo as a natural experiment for SAI, suggesting that sulfate aerosols could be artificially deployed to combat warming (Mills, 1992). The New York Times ran a piece that year exploring “man-made volcanoes,” quoting scientists like David Keith, who warned of risks like ozone depletion but acknowledged SAI’s potential. These stories introduced geoengineering to a broader audience, albeit as a distant prospect.

Government and Policy Stirrings

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) amplified the conversation with its 1992 report, “Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming.” Covered by The Washington Post, the report evaluated SAI alongside cloud brightening and space mirrors, estimating that 1–2 million tons of sulfur dioxide annually could offset warming (NAS, 1992). It flagged risks like acid rain but legitimized geoengineering as a research area. A 1993 Los Angeles Times article reported on congressional hearings where lawmakers debated SAI’s costs and ethics, with some viewing it as a fallback if emissions cuts faltered. These discussions, though niche, hinted at geoengineering’s future policy relevance.

Early Research and Military Speculation

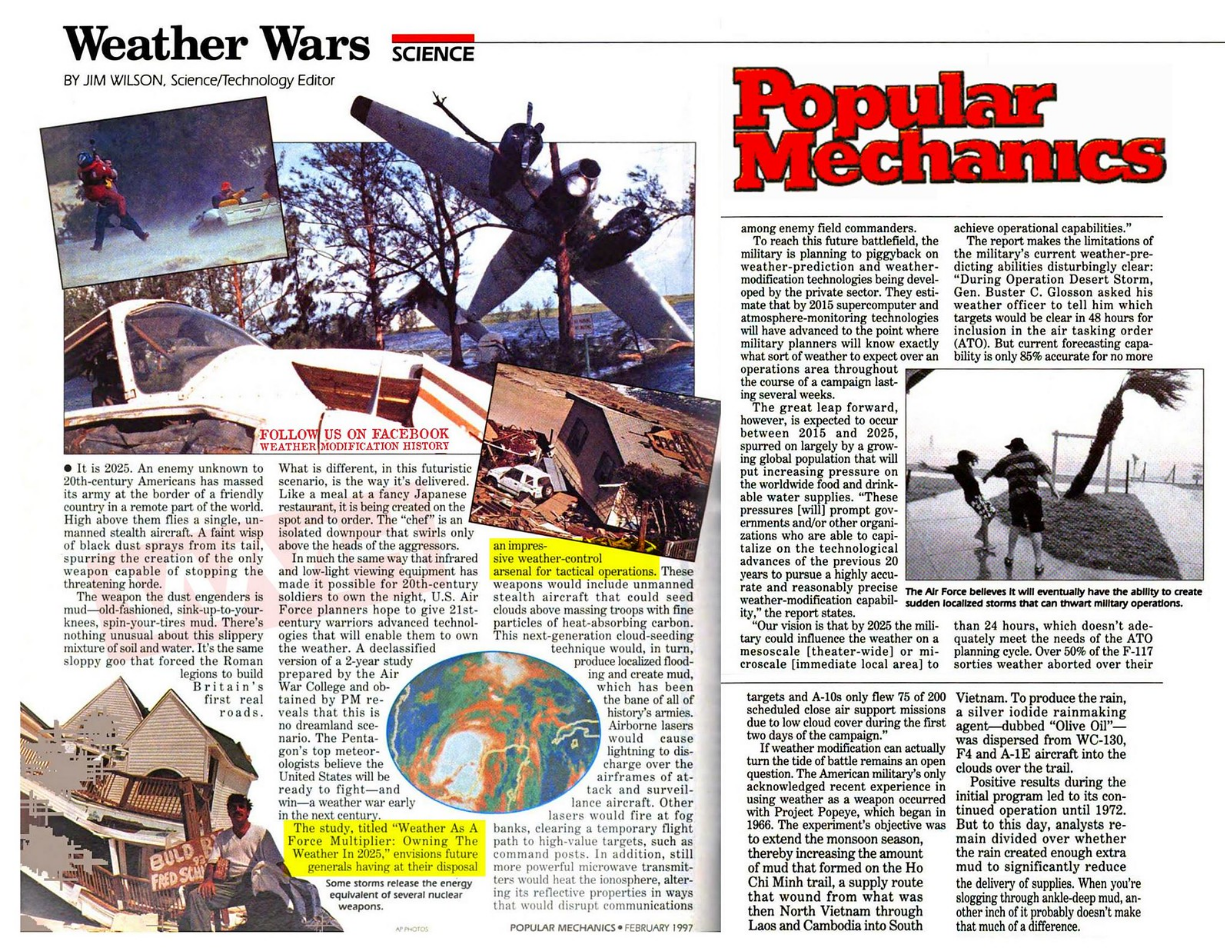

SAI research in the 1990s was mostly theoretical. A 1997 Nature study, covered by The Boston Globe, modeled SAI’s effects, warning of precipitation disruptions (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 1997). Edward Teller’s 1997 proposal to use stratospheric “scatterers,” reported by The Wall Street Journal, stirred controversy for prioritizing cost over ecological risks. Meanwhile, a 1996 U.S. Air Force report, “Weather as a Force Multiplier: Owning the Weather in 2025,” speculated about military weather control, including aerosols. Covered by Defense News, it fueled suspicions of covert programs despite its speculative nature.

Public Mistrust

With cloud-seeding as an active program in the US already underway for decades, it is no wonder that the chemtrails conspiracy “theory” soon emerged. By 1996, online essays and newsletters claimed that many aircraft contrails were actually chemical sprays for weather control. A 1996 The Oregonian article attempted to debunk these rumors, citing meteorologists who explained contrails as water vapor, but noted the traction of these theories in rural areas. People who grew up seeing contrails quickly dissipate after leaving a plane knew that the long trails that stayed in the air long after the airplane had passed were convinced that there was more than just water vapor in the trails crisscrossing the increasingly hazy sky. This skepticism, rooted in distrust of science and government, laid the groundwork for today’s conspiracies.

A Decade of Foundations

The 1990s, with climate change gaining global attention post-1988 IPCC formation and the 1992 Earth Summit, saw geoengineering emerge as a “Plan B.” Pinatubo provided proof-of-concept, and advances in modeling enabled simulations. While no SAI field experiments were openly admitted, cloud seeding and theoretical studies set the stage. Public mistrust, amplified by early internet forums, hinted at the challenges ahead. As Time magazine noted in 1998, geoengineering was a “futuristic fix” dividing scientists and activists, a divide that persists today.

Read part 2:

The True Story Behind the Chemtrail Conspiracy: Part II – From Fringe Theory to Mainstream Reality

I can tell you that the “cloud seeding” in southern Nebraska this April was unprecedented. There were more days in April with chemtrails than not (I should’ve kept track). Now we face a spring drought to the likes I’ve never experienced in my 40+ years of farming. I checked a field last night to dig up some corn seed and the top 2 inches are as dry as I’ve ever scratched by hand.

Cal, Famine has always been neck and neck with war in its ability to draw down a population