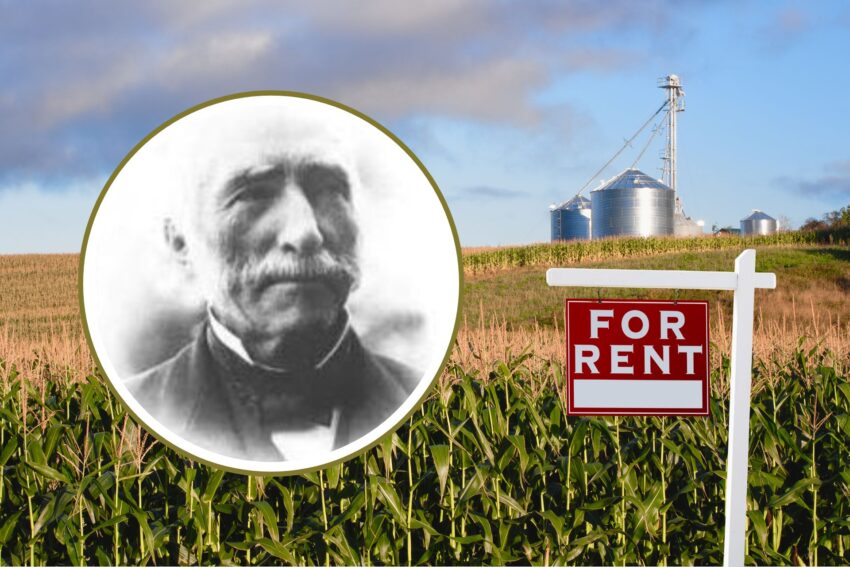

William Scully (1821–1906), an Irish-American landlord, etched his name into the annals of American agricultural history as one of the most formidable and controversial landowners of the 19th century. Through a combination of shrewd opportunism, exploitation of legal mechanisms, and an unrelenting drive to amass property, Scully built an empire spanning hundreds of thousands of acres across the Corn Belt. His methods, often unscrupulous, sparked deep resentment among farmers, while his descendants continue to wield significant influence over vast swathes of prime farmland to this day.

The Unscrupulous Rise of William Scully

Born into the lesser Irish gentry in 1821, Scully inherited wealth and a keen eye for land investment. After arriving in the United States in 1850, he set his sights on the fertile prairies of the Midwest, particularly in Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri—regions that would later become the heart of the Corn Belt. His approach to land acquisition was methodical and, at times, predatory, capitalizing on opportunities that others overlooked or were unable to seize.

One of Scully’s primary tactics was purchasing unused land warrants issued to veterans of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). These warrants, often sold cheaply by veterans who had no intention of farming, allowed Scully to acquire large tracts of land at a fraction of their value. By 1851, he had added over 21,000 acres to his Illinois holdings alone, laying the foundation for his vast estate. He also collaborated with newly established railroads, which had received extensive land grants from the federal government to encourage settlement and development. These railroads needed farmers to cultivate their lands, and Scully obliged by buying massive quantities—sometimes swampy or undeveloped—and transforming them into tenant-operated farms. His ability to snap up undervalued or marginal land, often before local settlers could organize to claim it, gave him an edge that many viewed as exploitative.

Scully’s absentee ownership further fueled perceptions of unscrupulousness. Rather than settling in the United States permanently, he managed his American properties from afar, employing agents to enforce his rigid policies. This detachment allowed him to prioritize profit over community ties, a stark contrast to the resident farmers who worked the land. By the time of his death in 1906, Scully owned approximately 225,000 acres, making him the largest individual landowner in the United States—a feat achieved through a combination of legal maneuvering, economic leverage, and an indifference to the struggles of those displaced or disadvantaged by his purchases.

Farmer Resentment in the Corn Belt

Scully’s sprawling land empire came at a steep cost to the farmers of the Corn Belt, igniting widespread resentment that simmered for decades. His tenant farming system, unconventional for its time, imposed harsh conditions that prioritized his financial interests over the welfare of those who worked his land. Unlike many landowners who offered sharecropping arrangements—where tenants kept a portion of the harvest—Scully demanded cash rents, payable regardless of crop yields or market conditions. This placed tenants in a precarious position, especially during years of drought or economic downturns, as they bore the full risk of farming while Scully’s income remained secure.

His leases were notoriously rigid: one-year terms ensured tenants had little stability, while requirements that they pay property taxes and fund their own improvements—such as buildings or drainage systems—shifted additional burdens onto their shoulders. Scully also insisted on soil conservation measures, which, while forward-thinking, were costly and labor-intensive for tenants who saw no long-term benefit from land they did not own. When tenants struggled to meet these demands, Scully was quick to employ crop liens and court actions to secure his payments, earning him a reputation for ruthlessness. Newspaper accounts from the 1880s and 1890s frequently vilified him as an absentee “land monopolist” who disregarded his tenants’ livelihoods. Many referred to him as ‘Skinner Scully’, ‘Tyrant Scully’ and ‘Lord Scully.’

Beyond his leasing practices, Scully’s sheer scale of ownership threatened the agrarian ideal of independent, small-scale farming that many settlers held dear. In an era when land ownership symbolized freedom and self-sufficiency, Scully’s dominance represented a return to feudal-like dependency. Farmers who hoped to purchase their own plots found themselves outbid or outmaneuvered by Scully’s deep pockets, while his refusal to sell land—preferring instead to lease it—locked generations into tenancy. This tension boiled over into public agitation, with Scully becoming a lightning rod for grievances against absentee landlords and foreign investors. State legislation in the late 19th century, aimed at curbing land acquisition by aliens, forced him to take American citizenship in 1900—just six years before his death—underscoring the depth of opposition to his practices.

A Lasting Legacy: The Scully Descendants Today

Scully’s death in 1906 did not mark the end of his influence. His meticulously crafted estate passed to his heirs, who have maintained control over a significant portion of his original holdings. While the exact size of the Scully estate has diminished over time—shrinking from 225,000 acres to an estimated 175,000 acres by recent accounts—the family’s grip on prime Corn Belt farmland remains formidable. Concentrated primarily in Illinois, with additional properties in Kansas and Nebraska, this land includes some of the most productive agricultural real estate in the United States, thanks to Scully’s early foresight in selecting fertile prairie soils.

The Scully descendants have adapted to modern times while preserving the core of their ancestor’s model. The estate continues to operate as a landlord enterprise, leasing land to tenant farmers under terms that echo William Scully’s emphasis on cash rents and strict management. Advances in drainage and agricultural technology have only increased the value of these holdings, ensuring the family’s wealth and influence endure. Unlike many large landowners who sold off parcels during the 20th century, the Scullys have largely resisted fragmentation, maintaining a cohesive empire that spans generations.

Conclusion

William Scully’s rise to power was a masterclass in exploiting opportunity, but it came at the expense of countless farmers who viewed him as an emblem of greed and oppression. His unscrupulous methods—snapping up land warrants, partnering with railroads, and enforcing draconian leases—secured his fortune while alienating those who toiled on his fields. The resentment he inspired in the Corn Belt reflected broader anxieties about land monopolies and foreign influence, yet his descendants have weathered these storms to retain control over a vast agricultural domain. Today, the Scully legacy is a complex tapestry of achievement and controversy, a testament to one man’s unrelenting pursuit of land—and the enduring impact of his choices on America’s heartland.