In the heart of American consumer culture, the rivalry between Coca-Cola and Pepsi has long been a staple, embodying the notion of choice in a market where, fundamentally, the options are more similar than different. This paradigm finds a curious echo in the realm of American politics, particularly in the spectacle of presidential elections.

The cola wars, famously heating up in the 1980s, saw Coke and Pepsi vying for supremacy, each with slight variations in taste, packaging, and marketing, yet both fundamentally offering the same product: a sugary soft drink. This battle for market share was less about profound innovation and more about capturing consumer preference through branding and minor tweaks. Similarly, U.S. presidential elections have become a battleground where candidates exclusively linked to one of the two dominant parties offer variations on policy themes. Still, the underlying system, which benefits the same power structures, remains largely unchanged.

In the political arena, much like choosing between Coke and Pepsi, voters often feel they’re making a significant choice when electing a president. However, this choice might be more illusory than real. The comparison here isn’t just superficial; it’s about the systemic nature of power dynamics. Just as cola companies tweak flavors or packaging, political parties adjust their rhetoric or focus issues, yet the core product—policy influenced heavily by lobbyists and special interest groups—remains consistent.

This analogy extends to a critique of the system itself. In a world increasingly aware of health implications, water represents the pure, essential choice over sugary drinks. In politics, this could be interpreted as a call for governance that focuses on the common good, free from the influence of corporate or special interest money. Yet, like consumers at a soda fountain, the American electorate often finds itself choosing between sweetened options, with neither side offering the ‘water’ of systemic change or genuine public service.

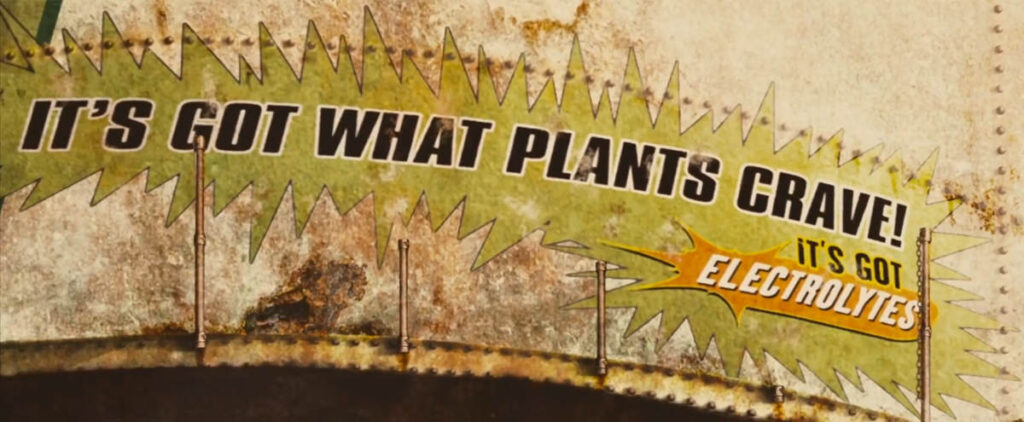

The movie “Idiocracy” provides a satirical yet poignant commentary on this scenario. In the film, the attempt to water plants with a sports drink, due to it having electrolytes, leads to disaster because of the salt content. This mirrors a political landscape where policies, much like the sports drink, are marketed with appealing attributes (“electrolytes”) but overlook the broader, often detrimental, impacts (“salt”). The political class, much like the future society in “Idiocracy,” might be so caught up in the immediate appeal of policy promises that they miss the broader, long-term harm.

The comparison between cola wars and U.S. presidential elections underscores a deeper critique of choice in American democracy. While the spectacle of elections and cola advertising campaigns offers an illusion of significant choice, the underlying mechanisms of both systems suggest a more uniform landscape, where true innovation or change is rare. Just as consumers might yearn for something as simple yet essential as water amidst a sea of sodas, the American public might find itself longing for a political landscape that offers governance for the sake of public welfare, not just the shifting of funds between the same circles of influence, as average Americans beg for scraps of our own tax money. In this light, the ongoing political “cola war” might be less about true choice and more about maintaining a status quo seasoned with the illusion of difference.

American voters often cast their ballot against a candidate they cannot stand rather than voting for one they honestly endorse wholeheartedly. It’s usually a question of who one considers the lesser evil, but is this really how democracy should work? What if we are being given two options that represent a false dichotomy? What if neither is good for us?